Note: This post was originally published in 2022. I’ve updated it and combined it with this year’s post about the Pinelands Short Course and Lines on the Pines and included dates for the 2024 events. Be sure to save the dates!

Across the bay from Brigantine Island lies the township of Galloway, one of my favorite places near the shore and in the Pine Barrens. As the reputed birthplace of the legendary Jersey Devil, Galloway is steeped in the bygone folklore of the Pines but is also the home of Stockton University, a relatively new but thriving center of learning. When I lived in Brigantine, I used to ride at Split Elm Equestrian Center located less than 10 minutes from the main campus and the base of Stockton’s Equestrian Team.

Galloway also hosts two days devoted to the Pine Barrens at Stockton’s main campus. In 2001, the annual Pinelands Short Course moved to Stockton for three years from its original home at Rutgers University’s Cook College where it debuted in 1990. It then returned to Rutgers until 2014 when it moved back to Stockton. I attended the event, described as “featuring educational presentations that explore the unique history, ecology, and culture of the Pinelands.” for the first time in 2022 when it returned after being canceled in 2020 just as the COVID-19 pandemic began sweeping the nation.

In April 2021, it took place virtually as a “short discussion” on Zoom hosted by the Pinelands Commission. Participants included:

- John Volpa, founder of the Black Run Preserve

- Ted Gordon, Botanist and Historian

- Terry O’Leary, Retired NJ Park and Forest Service Educator

- Becky Laboy, Education Outreach Specialist, Ocean County Soil Conservation District

- Samuel Moore, Cranberry Farmer and Retired NJ Forest Fire Service Warden

In 2022, I attended three presentations: Atlantic County’s Ghost Railroad: The Brigantine Railroad and Trolley System; Water and Wildlife: Pine Barrens and Barnegat Bay; and the Stockton Campus Birding Walk. Unfortunately, the weather was terrible with cold drenching rain in the morning switching over to a wintry mix later in the day.

Atlantic County’s Ghost Railroad

My first program of the day was Atlantic County’s Ghost Railroad: The Brigantine Railroad and Trolley System. Presented by Norman Goos, librarian for the Atlantic County Historical Society, this program delved into the history of the Brigantine Beach Railroad. From 1890 to 1910, the railroad connected Pomona in Galloway to the then sparsely populated island of Brigantine. Unfortunately, the railroad was short-lived. Plagued by storm damage, accidents, and labor issues, the rail company went out of business. Goos described how most of the tracks were removed for scrap during World War I.

Barnegat Bay

Next was Water and Wildlife: Pine Barrens and Barnegat Bay. This program was presented by Karen Walzer, Public Outreach Coordinator at Barnegat Bay Partnership. Karen described Barnegat Bay as a series of barrier islands, which are really “giant sandbars,” where the freshwater of the pinelands mingled with the salt water of the Atlantic ocean, creating a brackish ecosystem of tidal wetlands and salt marshes. Noting the threat of rising sea level, she highlighted the importance of wetlands as a buffer between the bay and nearby homes, protecting them from flooding and storm surge.

She also discussed the impact of pollution caused by overdevelopment and fertilizer runoff. Algae blooms, unhealthy growth of algae fueled by pollution, killed sea life. The end of Karen’s presentation focused on ways to protect and restore Barnegat Bay. Rain barrels, rain gardens, and green infrastructure mimicking nature help protect against runoff. Because shellfish such as scallops, oysters, and clams filter and clean water, efforts to control overharvesting, restore oyster reefs, and increase populations are underway.

I was particularly interested in this program because of Barnegat Bay’s ecological similarity to the backwaters of Brigantine, an area I’ve been familiar with since childhood. These coves, thoroughfares and channels are connected to Great Bay. Both Barnegat Bay and Great Bay are vital estuaries on the Jersey Shore.

Wet Winter Weather

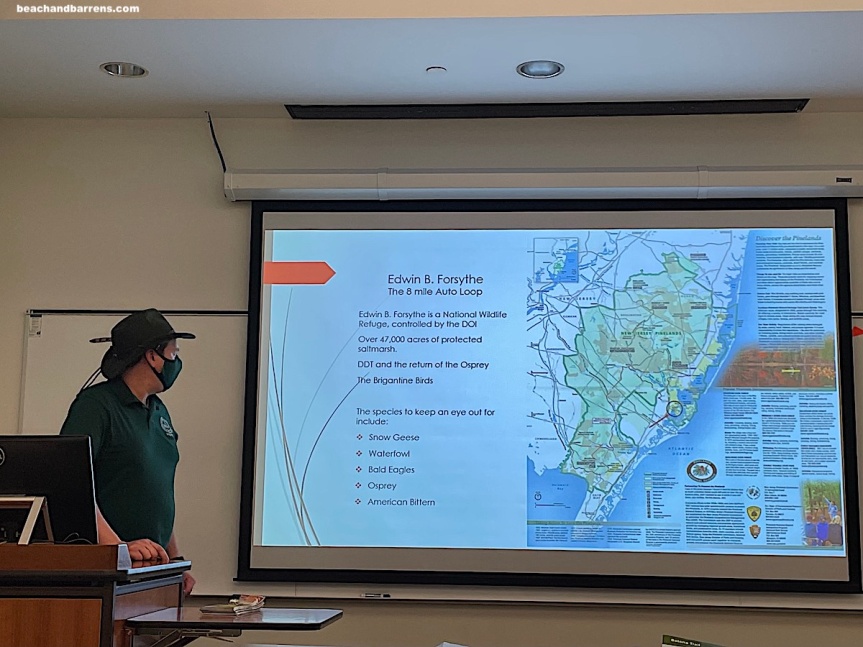

Because of the freezing wet winter weather, the Birding Walk was switched to an indoor presentation of best birding locations in and around the Pine Barrens. The presenter was Joshua M. Gant, a park naturalist with Ocean County Parks and Recreation.

In spite of the torrential rain, Jeff Larson, Pinelands Adventures’ most experienced tour guide and long-time Pine Barrens resident, led a bus tour of the historical ruins of Harrisville. A graduate of Stockton with a degree in business, Jeff told me that he designed and has conducted this tour for the short course since “about 2015” with the exception of the two years lost to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Originally called Ghosts of the Wading River, this year the program was renamed Harrisville: 19th Century Life on the Wading River. According to the description, this trip gives participants “a glimpse into what life was like along the Wading River in the Pine Barrens during the 1800’s. In this three-hour excursion, participants will explore the ruins in and around the former town of Harrisville and surrounding area.”

A professional guitarist and music teacher, Jeff composed two albums of music with a Pine Barrens theme: Leeds Devil Blues and The Barrens. In 2008, Jeff participated in Lines on the Pines as a musician. Billed as “an annual gathering of artists, authors and artisans whose passion is the Pines,” the event is free and open to the public.

Lines on the Pines

Linda Stanton started Lines on the Pines in 2006 after reading several books about the Pine Barrens. The first event was held at Sweetwater Casino where it remained until 2008. After a fire destroyed Sweetwater Casino, the event moved to various venues from 2009 and 2017 throughout Atlantic County, including the Frog Rock Golf and Country Club and Kerri Brooke Caterers in Hammonton as well as Vienna Inn and Renault Winery in Egg Harbor City. In 2018, the event moved to its current home at Stockton University where it takes place the day after the Short Course. I attended for the first time in 2019. As with the short course, the 2020 and 2021 events were canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

I’ve always been curious about the name of the event and reached out to Linda to find out what inspired it. “When I started the event it was to be a salute to authors who wrote about the Pine Barrens,” Linda explained. “Writing is lines, the topic is pines so I called it Lines on the Pines. This event is sponsored by my nonprofit: It’s a Sign of the Pines.”

Author and friend Barbara Solem has participated in Lines on the Pines every year the event has taken place since its inception where she offers her books for sale. Barbara is also a member of the Batsto Citizen Committee.

Musicians also participate in Lines on the Pines, beginning in 2007 with Valerie Vaughn, “New Jersey’s Troubadour,” and Jim Albertson, composer of Down Jersey, and continue to do so. Gabe Coia, composer of The Pines of My Past, played in 2008 with Jeff Larson and in 2012 with Renee Brecht. Gabe also plays at Batsto Village’s Winter in the Pines event. Other musicians and bands who featured their work at past Lines on the Pines include:

- Jim Murphy & The Pine Barons: Go New Jersey album

- G. Russell Juelg

- Bram Taylor

- Rich Carty (The Dulcimer Guy)

- Bryant Still-Hicks

- Ong’s Hat Band: Acoustic Roots Music on a Tangent

- Devin Wadell and Jake Perry: Elwood and Ocean Tide

- Tom Stackhouse: Tragedy. Mystery. Hope

Many more people and groups are represented each year, filling several rooms and drawing a large crowd. Here are some highlights.

Woodford Cedar Run Wildlife Refuge

The Woodford Cedar Run Wildlife Refuge, “a 171-acre wildlife refuge, wildlife rehabilitation hospital, and nature center” in Medford, had one of their resident Great Horned Owls with them to meet the public. I have visited Cedar Run several times, and I volunteered for them in a grant writing capacity during the pandemic.

Pine Barrens Diamonds

Paul Evans Pederson, Jr. is a local artisan who creates jewelry from glass found around the Pine Barrens left over from the days when glass factories were in operation. He calls his work “Pine Barrens Diamonds” and notes on his business card that he keeps South Jersey “glass-making traditions alive, using hand-made, hand-tooled” South Jersey glass. I mentioned to Paul that I lived in Atco, which had a glass factory in the past. He said he finds a lot of glass in Atco. I already have a pair of purple Pine Barrens Diamonds earrings purchased at a PPA event. Paul pointed out that purple was a rare color. I bought another pair of earrings made from multi-colored, opal-like glass.

Dr. James Still

Representatives from the Dr. James Still Historic Office Site and Education Center were on hand to discuss the mission of the center, which focuses on “teaching, restoring and preserving the Legacy” of the man known as ‘‘The Black Doctor of the Pines.” Dr. Still was a 19th century physician who built a successful medical practice in the Pine Barrens despite the racism and prejudice he faced. The center, located in Medford on the site of Dr. Still’s office is “the first African American Historic Site preserved by the state of New Jersey.” It will open on the first and third Sundays of each month from noon to 4 p.m. Books about Dr. Still available for purchase at the center include:

- Early Recollections and Life of Dr. James Still by Dr. James Still

- The Underground Railroad by William Still

- The Kidnapped and the Ransomed: The Narrative of Peter and Visa Still after Forty Years of Slavery by Kate E.R. Pickard.

Iron, Glass, and Horses

Earlier this year, I attended the Pinelands Short Course once again in March. This year John Hebble, Historian at Batsto Village, gave a presentation entitled Iron, Glass, And Water: Industry And Natural Resources In The Pine Barrens.

After giving an general overview of the ecological region known as the Pine Barrens and the area covered by the Pinelands Comprehensive Management Plan, John discussed how the ample supply of water in the Pine Barrens enabled several major industries to thrive leading to the establishment of industrial towns such as Batsto Village.

Batsto Village was founded as an iron furnace in 1775, utilizing ready access to water and pitch pine for charcoal to process the bog iron ore found in the Pine Barrens. John displayed photos of advertisements of the era, describing how the furnaces at both Batsto and Atsion produced and sold such items as iron cookware and tools “of the best quality.” John also described the system of indentured servitude that provided workers for the ironworks.

Next, John discussed the importance of South Jersey glass, which developed after the bog iron industry declined. Three major natural resources allowed the glass industry to thrive in the Pine Barrens: sand, wood, and navigable waterways. From 1840 to 1860, almost one-third of the glass in the United States was manufactured in New Jersey. Glass-making became one of the oldest and most successful industries in South Jersey.

The Batsto Glass Works operated from 1846 to 1867. Jesse Richards and his son Thomas H. Richards constructed the glassworks near the furnace. John said Batsto produced glass primarily for windows and street lamps such as the thousands of street lamps installed in Camden in 1852.

In addition to John’s presentation, I registered for two other classes during the day, including Where the Pinelands Meet the Bay: the Unnoticed Symbiosis of Shellfish and Pinelands, presented by Rick Bushnell, Chair of ReClam the Bay. Rick discussed the relationship between Barnegat Bay and the Pinelands where the eastern edge of the pines touches the western edge of the Barnegat Bay estuary and explained how shellfish help protect against erosion.

“Everything’s connected,” he said and described the mission of his organization. According to the Reclam the Bay website: “We grow and maintain millions of baby clams and oysters in the Barnegat Bay Watershed which includes Barnegat Bay, Manahawkin Bay and Little Egg Harbor bay. We want people to understand the services that shellfish provide. They filter water, provide habitat, stabilize shorelines, and TASTE GREAT. Help us give them a better home so they can give us a better home”

I also attended a presentation of live raptors from Woodford Cedar Run Wildlife Refuge, including a broad-shouldered hawk, great horned owl, and turkey vulture. Cedar Run rehabilitates injured wildlife with the goal of releasing them back into the wild. When an animal is not able to recover sufficiently to allow for that, as was the case with these three birds, Cedar Run gives them a permanent home and sometimes takes them on educational trips such as this one.

At the end of the day, I listened to a performance in the Campus Center cafe by Jackson Pines. Founded in their hometown, the Pine Barrens municipality of Jackson in Ocean County, this folk band played New Jersey folk songs on guitar, stand-up bass, fiddle, and harmonica. Tunes covered included Mt. Holly Jail, the Unquiet Grave, Depression Song, Love is a Gamble, Beulah Land, and Clam Diggers Blues.

The next day I attended the 2023 version of Lines on the Pines. This year’s theme was “Hoof n’ Tell,” paying homage to horses, the state animal of New Jersey since 1977.

I was honored that Linda Stanton asked me to contribute two articles, Ghosts of Horse Racing’s Past and Our Gal Sal, to a short book she compiled for this year’s event entitled Horses of New Jersey’s Pine Barrens: Stories and Tall Tales By the Pine Barrens Celebrities of Lines on the Pines. Linda dedicated the book to her late husband, Jim Stanton. I got to meet Linda in person for the first time, and she was kind and gracious enough to sign my copy of the book for me.

The book contains articles and poems with a horse theme along with photos and artwork. Other contributors include South Jersey Horse Rescue in Egg Harbor City, Funny Farm Rescue & Sanctuary in Mays Landing; C. Paul Evans Pederson, Jr. (Mount Misery Music, BMI and Pine Barrens Diamonds); historian John Hebble; Wes Hughes of the Batsto Citizens Committee; and Budd Wilson. The book’s introduction explains that a group of students from Our Lady of Victories School in Harrington Park suggested designating the horse as the state animal where it is now proudly represented on the state seal as a horse head, symbolizing “speed and strength.”

I also met Dr. Thomas Kinsella, Director of Stockton’s South Jersey Culture and History Center (SJCHC), who assists Linda with the event. The SJCHC publishes SoJourn magazine, which focuses on South Jersey history and culture. Kinsella invited me to contribute an article in a future edition. Stay tuned!

Save the Dates!

The 35th Annual Pinelands Short Course is scheduled for March 9, 2024. Lines on the Pines, held the second Sunday of every March, is scheduled for March 10, 2024.